As the coronavirus has attacked and panicked publics worldwide, it has also served to remind them about the value of scientific expertise. One of the striking patterns in global public opinion is the extent to which publics are placing their faith mostly in scientists and other health science experts to provide them with the information they need about the outbreak. Even in the US, where belief in science has partly fallen victim to partisan polarization, there is evidence that Americans of all partisan affiliations primarily trust health scientists to provide accurate information on the disease.

This is the nineteenth in a series of regular papers from GQR analyzing all globally available data on opinion on COVID-19, with a particular focus on the political implications of global opinion linked to the pandemic.[1] Earlier editions are here. Major insights in this edition include:

- The pandemic has raised questions for publics worldwide about who they trust to provide accurate and useful information about public health. Scientists and health authorities worldwide have generally emerged as the most trusted sources of information – even in the US, where trust in science has partly fallen victim to political polarization.

- The October 1 announcement that President Trump tested positive for COVID-19 raises the question of how leaders’ public images change if they contract the virus. The three most significant national leaders who have now contracted the virus – Trump, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, and Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro – are now also the only three major world leaders to see their approval decline since the start of the pandemic.

- Recent elections in Kyrgyzstan, Lithuania, and the Czech Republic show differing political impacts from the pandemic. The most important case is Kyrgyzstan, where dissatisfaction with the government’s handling of the pandemic helped fuel public protests after the government held a tainted election; just today, the country’s president has stepped down, and the country will now hold new elections.

Major Insights

The pandemic has raised questions for publics worldwide about who they trust to provide accurate and useful information about public health. Scientists and health authorities worldwide have generally emerged as the most trusted sources of information – even in the US, where trust in science has partly fallen victim to political polarization.

The pandemic has had the worldwide effect of underscoring the importance of science and scientists, and generally raising public regard for institutions linked to science and health. In many countries, the top experts on the coronavirus – like Dr. Anthony Fauci in the US, Dr. Christian Drosten in German, Dr. Fernando Simón in Spain, or Dr. Jaap van Dissel in the Netherlands – have become admired household names.

An April study by Oxford University and Reuters Institute, examining attitudes in the US, UK, Germany, Spain, Argentina, and South Korea, finds that in five of these six countries, “scientists, doctors, and health experts” are the most trusted source of information about the coronavirus outbreak. In all six countries, at least 74% trust these experts, and the figure is at least 80% in all but Germany. Only the British do not rank these experts as the most trusted source of information; they place marginally more trust in “national health organizations,” trusted by 89%, compared to 87% for scientists.

In all six countries, news organizations are trusted much less – they rank 3rd, 4th, or 5th, out of eight sources of information tested. “Politicians” rank second-to-last, on average across the six countries; only “people I do not now” rank lower.

An October 5 Kantar poll in Sweden finds that even in that country, which has pursued one of the most relaxed policy responses to the pandemic among developed countries, the public trusts scientific experts the most: 77% trust health experts, and 75% trust the Swedish Public Health Agency, compared to only 45% who trust the government.

In the US, a June 22 New York Times/Sienna poll finds that Americans put the greatest trust in “medical scientists,” trusted by 84%, which is greater than for the federal Centers for Disease Control (77%), or Dr. Anthony Fauci (67%).

In the US, more than in other countries, trust in science has recently fallen prey to the broader forces of partisan polarization. According to research from Pew and NORC’s General Social Survey, Democrats and Republicans had comparable confidence in the scientific community as recently as 2006; but Democrats now have significantly more trust in the scientific community – by about 10 points. Yet, despite this polarization of views about science (especially on issues like climate change), public faith in scientists on the pandemic crosses US party lines. In the NYT/Sienna poll, the dominant trust in medical scientists holds true across Democrats, Independents, and Republicans alike.

Mirroring the NYT/Sienna findings, a September 3 Kaiser Family Foundation poll finds that the American public has the greatest trust in Dr. Anthony Fauci (68% trust him “a great amount” or “fair amount” to “provide reliable information on coronavirus”), with the CDC coming in second (67%). (The KFF poll did not test “medical scientists.”) While trust in both has declined somewhat since April, it has dropped much more for the CDC (down 16 points) than for Dr. Fauci (down 10 points), possibly reflecting the CDC’s series of missteps and reversals on its policy guidance.

As in other countries, American politicians are far less trusted than the health experts. In the KFF poll, a 51% majority trust Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden, lower than the health experts; but the figure is even far lower, only 40%, for President Donald Trump.

The October 1 announcement that President Trump tested positive for COVID-19 raises the question of how leaders’ public images change if they contract the virus. The three most significant national leaders who have now contracted the virus – Trump, British PM Boris Johnson, and Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro – are now also the only three major world leaders to see their approval decline since the start of the pandemic.

The October 1 announcement that President Trump had tested positive for COVID-19 raised immediate questions of how contracting the disease might affect his political standing – whether it would generate a “sympathy bump,” or whether it would deepen the sense that he has been negligent in dealing with the pandemic.

Global polling shows a consistent pattern on this kind of question. At this point, three major world leaders have contracted the disease – Trump, British PM Boris Johnson, and Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro. The latter two both announced their positive test results in March. All three have saw a decline in their standing immediately after testing positive (Bolsonaro’s ratings have rebounded slightly, but only long after his bout with COVID-19).

It is notable that these three leaders also responded to the coronavirus outbreak with populist messages and a relative lack of what Oxford researchers call “stringency” in recommending policy responses. As previous editions have noted, voters in most countries have rewarded stringent responses and leader messages that rely more on science than populism.

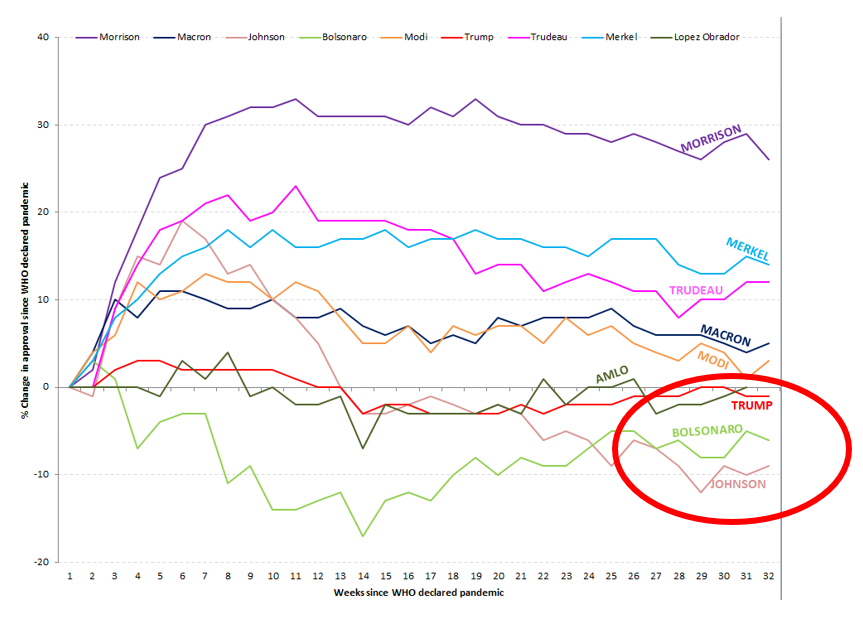

As Figure 1 shows, these three are now the only top world leaders in our tracking who have seen their approval ratings decline since the pandemic was first declared on March 11. This pattern suggests that contracting COVID-19 does not lead to public sympathy or a rise in approval ratings. If anything, contracting COVID-19 may have deepened public perceptions that these three leaders were careless about the virus – at the level of both public policy and their own personal health.

Figure 1: Changes in approval ratings for major world leaders since March 11 (data from Morning Consult; format courtesy of The Economist)

Recent elections in Kyrgyzstan, Lithuania, and the Czech Republic show differing political impacts from the pandemic. The most important case is Kyrgyzstan, where dissatisfaction with the government’s handling of the pandemic helped fuel public protests after the government held a tainted election; just today, the country’s president has stepped down, and the country will now hold new elections.

As we have noted in previous editions, the most politically important measurement of public opinion regarding the pandemic comes not from polls but from election results. For that reason, this series of papers has monitored all significant elections since the pandemic started to analyze the impact of the outbreak. Over the past two weeks, since our last edition, national elections in Kyrgyzstan, Lithuania, and the Czech Republic have produced additional insights on the political impact of the pandemic.

Kyrgyzstan parliamentary election, October 4. The most interesting case is Kyrgyzstan, which held parliamentary elections on October 4. The elections were widely viewed as not free and fair, and for the third time in 15 years the country erupted into protests following fraudulent voting. Observers recorded “numerous and significant” issues with the voting process. Yet election dynamics and the public reaction to the declared outcome show major impacts from the coronavirus outbreak.

When the Central Election Commission reported that three of the four parties allied with authoritarian President Sooronbay Jeenbekov had been elected to parliament, the public concluded the results were fraudulent and thousands took to the streets. The police cracked down hard on protesters, with tear gas, water cannons, and stun grenades.

But protesters fought back, seized the Parliament building in Bishkek, ousted the Prime Minister, demanded a repeat of the vote, and sprung from jail a popular leader, Sadyr Zhaparov. The Election Commission nullified the election results, President Jeenbekov agreed to appoint Zhaparov as Prime Minister, and just today Jeenbekov stepped down from the presidency, making Zhaparov the de facto leader of this country of over 6 million.

Recent events and polling suggest frustrations with the government’s response to the coronavirus played a role in these events. Early failures in the government’s response led to the dismissal of the Health Minister in April (and his eventual arrest for negligence and abuse of office). Kadyr Toktogulov, former Kyrgyzstan Ambassador to the United States and Canada, said the government’s handling of the pandemic “was seen as disastrous.”

In an August poll by IRI, a majority (53% – up significantly from 36% in 2019 and 27% in 2018) saw the country going in the wrong direction, especially in urban areas like Bishkek. An even stronger 67% were dissatisfied with the government’s response to coronavirus. Though most cited the economy as one of the top concerns facing the country (61%), a 51% majority cited the coronavirus outbreak as well.

The government also used the pandemic to advance anti-democratic measures. In the important report from Freedom House discussed in last week’s edition, one expert on Kyrgyzstan notes that the government has taken the opportunity to pass laws restricting freedom while society is “distracted” by coronavirus. Several Kyrgyz experts in the report cite a new bill, “On Manipulating Information,” as a major challenge for democracy in Kyrgyzstan. The vague nature of the bill gives authorities the ability to block any sites that they deem contain untrue information. A joint statement from the OSCE, UN, and IACHR raised concerns about the accessibility of information on COVID: “Human health depends not only on readily accessible health care. It also depends on access to accurate information about the nature of the threats and the means to protect oneself, one’s family, and one’s community.”

Lithuania parliamentary election, October 11. Lithuania’s parliamentary election provides a case in which a government’s generally positive handling of the pandemic was insufficient to prevent it from losing power. In that balloting, the opposition conservative party, Homeland Union, claimed victory in the first round of elections, winning 23 seats, while the ruling coalition, Lithuanian Greens and Farmers Union (LGFU), fell to second place with 16 seats.

Support for the LGFU had dropped before the pandemic hit, and was already hovering in single digits by the end of 2019. Yet it may be that the efforts of the LGFU government to combat the coronavirus helped the LGFU avoid even bigger losses. The Lithuanian government has made use of economic assistance payments and bonuses for medical workers and pensioners, and these may have helped prevent an even more lopsided result.

It is notable that turnout, at 47%, was only 3 points lower than in Lithuania’s 2016 election, despite health concerns created by the pandemic.

Czech parliamentary election, October 11. The Czech elections also produced a mixed picture, in terms of the political impact of the coronavirus. Prime Minister Andrej Babis’s ruling ANO party was able to retain control in regional elections, but voters handed the Senate – which controls constitutional issues – to the opposition, with opposition party Mayors and Independents winning the most seats for any one party. ANO and its coalition partner, Social Democrats, together captured only one seat. The opposition’s strength partly reflected its efforts to capitalize on rising public concern about a new surge in COVID-19 cases.

According to a September poll by CVVM, the 74% share who are concerned about their friends and family contracting the virus is up 10 point from June, as the number of cases has recently spiked. PM Babis has faced criticism from his opponents that he has been too hesitant to bring back stricter quarantine measures. (Soon after the election results were announced, Babis announced a second lockdown.)

As in Lithuania, concerns over COVID-19 did not dampen Czech voter turnout, which was up slightly from similar elections in 2016.

[1] These papers are not exhaustive in summarizing all aspects of the global opinion research. Instead, we focus on selected aspects of available global opinion research, with an emphasis on political implications, and provide links to all polls identified, so others have a resource for their own investigations. Our first 18 installments of Pandemic PollWatch, from March 20 through October 2, reviewed a total of 1,811 polls from 110 different geographies (generally countries, but also polling for Hong Kong and various states and provinces). This week’s analysis reviews an additional 88 polls, covering 28 geographies. Links to all polls reviewed are listed here. As the Appendix notes, the polls reviewed vary significantly in methodology and reliability.

Appendix

This analysis is based on available global public opinion research on the COVID-19 pandemic. We welcome input from others – including insights about opinion trends and dynamics, and about additional public opinion research that is not included here.

Countries and territories with published public opinion data on COVID-19 at this point include:

- Afghanistan

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belarus

- Belgium

- Benin

- Bolivia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Cameroon

- Canada

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cote d’Ivoire

- Croatia

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Denmark

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Estonia

- Ethiopia

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Guinea-Conakry

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- Iceland

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Liberia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Malta

- Mexico

- Montenegro

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- The Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- North Macedonia

- Norway

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Senegal

- Serbia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sudan

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Tunisia

- Turkey

- Uganda

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Zambia

- Zimbabwe

The reliability of the public opinion data from these geographies varies – and affects the analysis – for several reasons. First, some of these countries, such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, are “not free” (according to rankings by Freedom House) and respondents in these countries may not feel free to give their actual opinions in a survey.

Second, some of the polling organizations quoted in these reports may have stronger or weaker records regarding accuracy, methodological rigor, transparency, and other procedural factors that affect the reliability of their findings.

Third, the methodologies used in these surveys vary, and few are “gold standard” quality. The pandemic has driven researchers in most geographies to rely on online surveys, which generally do not have probability-based samples and can suffer from opt-in bias. Sample sizes and quality control procedures also vary across the available surveys.

The 18 earlier editions of Pandemic PollWatch, available here, include links to all the previous COVID-19-related polls summarized in this series.

All polls reviewed so far, including in this edition, can be found in the full bibliography here.