an analysis of global public opinion on covid-19

The coronavirus kills more men than women worldwide; but many of its economic impacts disproportionately hurt women. Are there clear gender differences as well in global attitudes toward the pandemic?

This week’s edition of Pandemic PollWatch examines how men and women around the world view the coronavirus crisis differently, including on both the health and economic consequences. It is the twelfth in a series of weekly papers from GQR analyzing all globally available data on opinion on COVID-19, with a particular focus on the political implications of global opinion linked to the pandemic.[1] Earlier editions are here. Major insights in this edition include:

- From the early days of the pandemic, women in a large number of countries expressed somewhat more concern over the coronavirus, compared to men.

- Nearly three months into the pandemic, many gender differences persist, although differences are often small and narrowing in some places.

- In many cases, much of the gender disparity in attitudes likely traces back to gender gaps in the country’s partisan outlook.

- Beyond gender differences, this week’s tracking of global polls shows a gradual but sustained rise in the share of countries where public concern about contracting COVID-19 is increasing. It also shows a gradual drop in approval ratings for national governments worldwide on their handling of the pandemic. These trends may reflect fears about a second wave of COVID-19, frustrations about the economic downturn, or other factors.

Major Insights

Several analyses have noted that the coronavirus pandemic is attacking men and women differently. Although country-to-country data sets on this are of uneven quality, there is strong evidence that COVID-19 is killing more men than women. Global Health 50/50, housed at University College London, finds “a consistent pattern of higher death rates recorded among men compared to women.”

There are also gender differences in the pandemic’s economic and social impacts. In the US, federal government data show that, for various reasons, women have borne the majority of job losses. A World Bank study suggests that women will suffer a differential economic impact globally, due to their child-bearing and child-raising roles, and because large portions of women in many countries work in the sectors that will be hard-hit by layoffs and that provide few work benefits or social supports.

Do these gender-based differences in the health, economic, and social impacts of the virus translate into gender differences in attitudes toward the pandemic? The answer is: perhaps.

In many countries, polls show that women are more concerned about the health impacts of the coronavirus, and often more hesitant to pursue economic reopening. But the differences are often relatively small. And it is not clear how much these differences result from gender independently, as opposed to gender gaps in partisan preferences in many of the countries for which polling data is available.

From the early days of the pandemic, women in a large number of countries expressed slightly more concern over the coronavirus, compared to men.

Multi-country surveys near the start of the coronavirus outbreak revealed some gender differences, although they were not extreme. For example, an Ipsos April 4 survey across 15 countries (Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Russia, Spain, UK, US, Vietnam) found 80% of women, compared to 75% of men, said they were likely to self-isolate, in reaction to the threat of COVID-19.

Many early country-specific polls also revealed somewhat more concern among women. A March 22 Monmouth University poll in the US found 45% of women were “very concerned” about “someone in your family becoming seriously ill from the coronavirus outbreak,” compared to 31% among men. Yet, despite the higher job losses among women in the US, among respondents in the Monmouth poll who said the pandemic had a “major impact” on their daily life, men were more likely than women to say that the impact was a reduction in work/income – 38% among men, but only 24% among women.

Early surveys in other countries echo the higher level of concern among women. A March 24 JL Partners poll in the UK found that 37% of British women were “very much concerned” (10, on a 1-10 scale) about the impact of coronavirus on their personal health, compared to 26% of men.

A March 24 Elabe poll in France found 38% of women, but just 24% of men, were personally very concerned about the coronavirus.

An April 2 Novus survey in Sweden found 31% of women were very or quite worried about the coronavirus, compared to 23% of men.

A March 6 Angus Reid poll in Canada found higher concern particularly among younger women. Among women ages 18-34, 38% felt there was a “serious threat of a coronavirus outbreak in Canada,” compared to just 28% of men in that age bracket.

Nearly three months into the pandemic, many gender differences persist.

As people in more countries adjust to living under the threat of COVID-19, and as the focus of attention in many countries turns to economic and social reopening, many gender differences persist.

In a May 8 survey by Geopoll across 11 sub-Saharan African countries (Benin, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa, Uganda, and Zambia), concern about the coronavirus spreading in each place was at least somewhat higher among women than men in 9 of the 11 countries. But the differences were small. The average difference in the level of concern between men and women across the 11 countries (not weighted for population) was only 3 points, and in only 2 of the 11 countries was the difference more than 5 points.

Similarly, a May 10 Ipsos poll in 16 countries finds that some negative behavioral responses to COVID-19 are more common among women. Across most of the tested negative reactions, women in a majority of the countries were more likely to report having experienced the following “as a result of COVID-19”: migraines (women more likely to report them in all 16 of the 16 countries); anxiety (in 15 of 16 countries); insomnia (15 of 16); over-eating (14 of 16); depression (13 of 16); and under-exercising (12 of 16). There were only three negative behaviors – under-eating, increased smoking, and increased alcohol use – where women were not more likely than men to report an increase in most of the countries surveyed. But, again, the differences in many of these cases were small, likely below levels of statistical significance.

There is evidence that, in some specific countries, the earlier gender gaps on COVID-19 have remained.

In Sweden, for example, the 8-point gap in the Novus poll noted above between women and men on being very/quite concerned about the pandemic, has stayed relatively steady, moving to 9 points (37% for women, 28% for men) in Novus’s May 3 survey.

In Australia, a May 24 Essential Research poll finds that only 20% of women believe the government should start easing economic and social restrictions “as soon as possible” or “within the next 1-2 weeks,” compared to 29% of men. That 9 point gap is roughly the same as the 7 point gap on this question in Essential’s May 3 polling.

A May 26 Datafolha survey in Brazil finds women are 7 points more likely than men to say it is more important to “[keep] people at home to prevent the coronavirus from spreading even if it damages the economy and causes unemployment,” with 68% of women saying this, compared to 61% of men.

In the UK, a May 28 ORB poll finds men are 10 points more likely to believe the spread of the virus in the UK is now under control (38% of men compared to 28% of women). A May 28 YouGov poll finds women are 6 points more likely than men to say that “trying to save every life” matters more than “protecting the economy,” 68% among women, and 62% among men. Yet the poll does not show evidence of a differential economic impact, with women and men equally likely to say they have lost their job or faced a reduction in pay/hours because of the pandemic.

In a set of May 24 Redfield and Wilton polls in France, Germany, and Italy women across the board feel less safe returning to work, or even leaving their homes at all.

A May 18 About People survey in Greece finds that, since the country began reopening on May 4th, women are less comfortable returning to three of eight kinds of economically and socially important activities: going to the salon or barber, patronizing small shops, and visiting the supermarket. But on five others (using public transportation, attending church, going to large stores, shopping at small grocers, going to banks) the results were roughly comparable, or women felt more comfortable.

In Canada, the gender gap may have grown somewhat. In an April 17 Angus Reid poll, women were 6 points more likely to say the government should focus on health more than the economy, with 55% of women saying this, compared to 49% of men. In their June 3 polling, the gap is much wider, 17 points – with 59% of women focused on the economy, and just 42% of men.

In other countries the gender gap remains, but has closed somewhat. For example, in France, a March 31 Opinion Way survey revealed a 12-point gap on levels of high concern about COVID-19 – 36% of women rated their concern a 9 or 10 out of 10, while 24% of men did. In their June 2 poll, however, there has been a drop in both the absolute levels of concern and the gap between men and women – 22% among women, 17% among men.

In the US, substantial gender gaps persist in a range of questions regarding COVID-19. But as the next section concludes, these are often explained by partisan differences between men and women. Indeed, it is remarkable that – given the large political gender gap in the US – there are some aspects of the pandemic on which men and women in the US largely agree. For example, a May 25 Russell Research poll finds men and women about equally concerned about COVID-19 (85% among men, 87% among women), and that this has been generally true since their tracking began in early March.

In many cases, however, much of the gender disparity in attitudes likely traces back to gender disparities on partisan preference.

Although the gender differences above are notable, it may well be that, in many countries, they reflect less about gender-based differences in views of the coronavirus, and more about gender gaps in partisanship. Particularly as the pandemic has become more of a political issue, gender gaps on partisan preference may be partly or fully driving gender differences in perception of the pandemic.

For example, in the US, a June 1 Politico/Morning Consult poll finds that women are slightly more likely than men to say they are more concerned about “the public health impact of coronavirus,” as opposed to “the economic impact”; 59% of women say this, compared to 54% of men. But there are no significant differences between men and women in each party. Rather, the overall gender difference is driven by the fact that women are much more aligned with the Democratic Party, and self-identified Democrats much more strongly care about the pandemic’s health impacts.

Even in the thick of the pandemic, an April 19 GQR poll showed no real differences between Democratic men and women or between Republican men and women on whether they are more concerned about the spread of the disease or the impact on the economy. In that same survey, Democratic women are 15 points more likely to be “very worried” about personally contracting the coronavirus compared to Democratic men. Republican women were less concerned about this than Democratic women, reflecting their partisanship, but still are 8 points more “very worried” than Republican men.

In the US, UK, Canada, Australia, Sweden, and many other key countries, women tend to favor the center-left party (Democrats in the US; Labour in the UK; Liberals and the NDP in Canada; Labor in Australia; and Social Democrats in Sweden). Those differences in many cases are sufficiently large to explain the gender disparities on questions regarding COVID-19, particularly on issues that have become polarized in partisan terms, such as approval of the government’s job in handling the pandemic or agreement on the pace of the government’s economic reopening policies.

In other countries, where the partisan gender gap is less pronounced, there are also fewer gender differences on questions linked to the government’s handling of the pandemic. For example, Germany and Italy have both seen relatively minor gender differences in recent elections and polls. In a set of May 24 Redfield and Wilton polls in these countries, there is also little gender difference on many matters related to the pandemic. In Germany, the government’s handling of the pandemic are very close: 79% of men say the government handle the crisis well, compared to 76 % of women. Similarly, in Italy, 58% of men believe the government handled the crisis well compared to 55% of women.

Beyond gender differences, this week’s tracking of global polls shows a gradual but sustained rise in the share of countries where public concern about contracting COVID-19 is increasing. It also shows a gradual drop in approval ratings for national leaders worldwide on their handling of the pandemic. These trends may reflect fears about a second wave of COVID-19, frustrations about the economic downturn, or other factors.

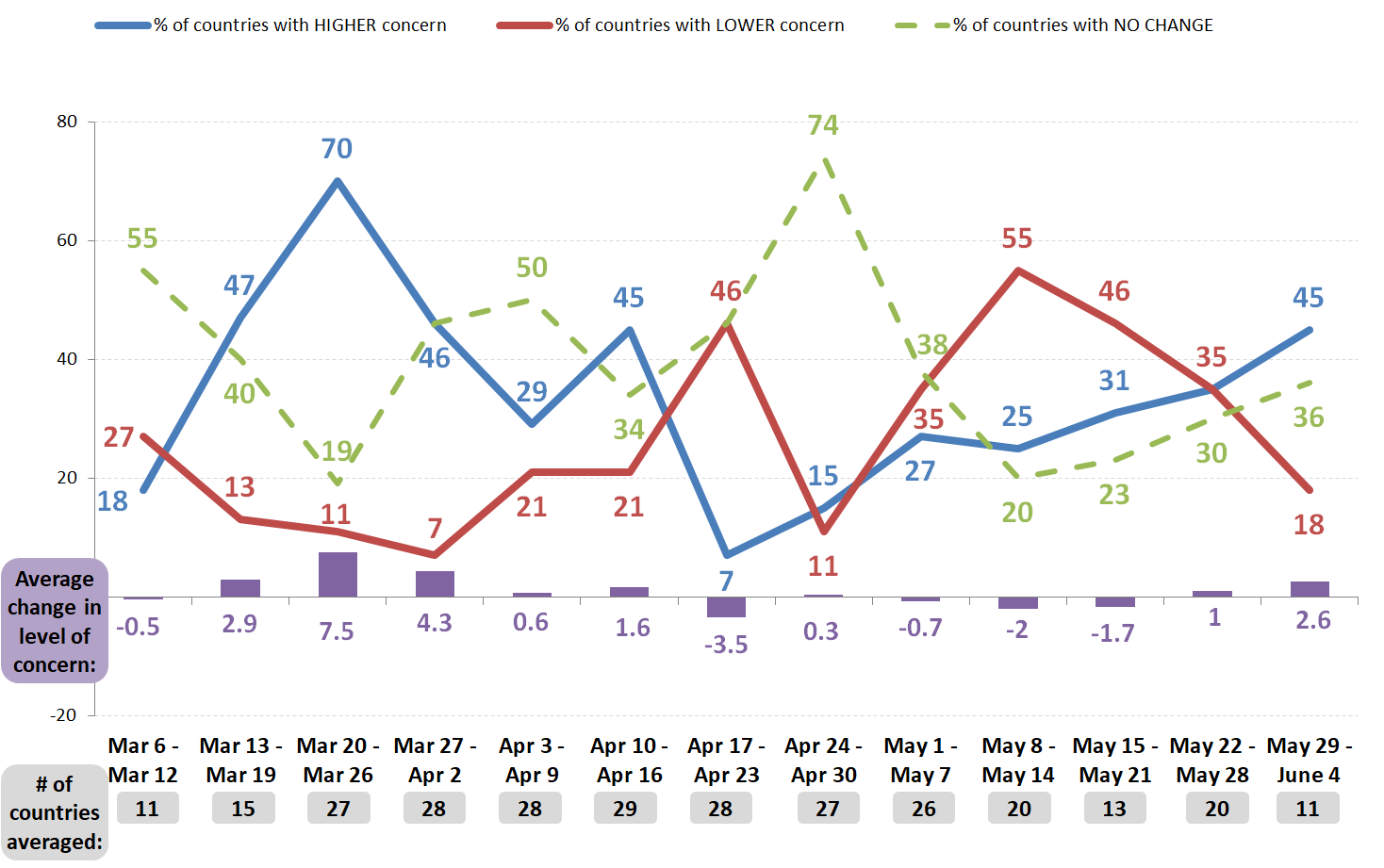

Worldwide concern about contracting COVID-19 spiked in mid-March. As Figure 1 shows, by the week of April 17-23, levels of concern had started to subside, with the level of concern dropping by an average of 3.5 points, across the 28 countries surveyed that week (not weighted for population).

Over the past two weeks, however, concern has begun to rise again. This week the average worldwide increase in concern is 2.6 points – the biggest increase since the week ending April 2. For the first time since the end of April, more countries report a major increase in concern (a rise of at least 3 points) than report a decrease. This is a notable and worrisome development. It may reflect early signs of a resurgence of the disease, anticipatory concerns over a “second wave” in late 2020, or some other factor.

Figure 1: % of countries showing increase/decrease in concern over contracting COVID-19[2]

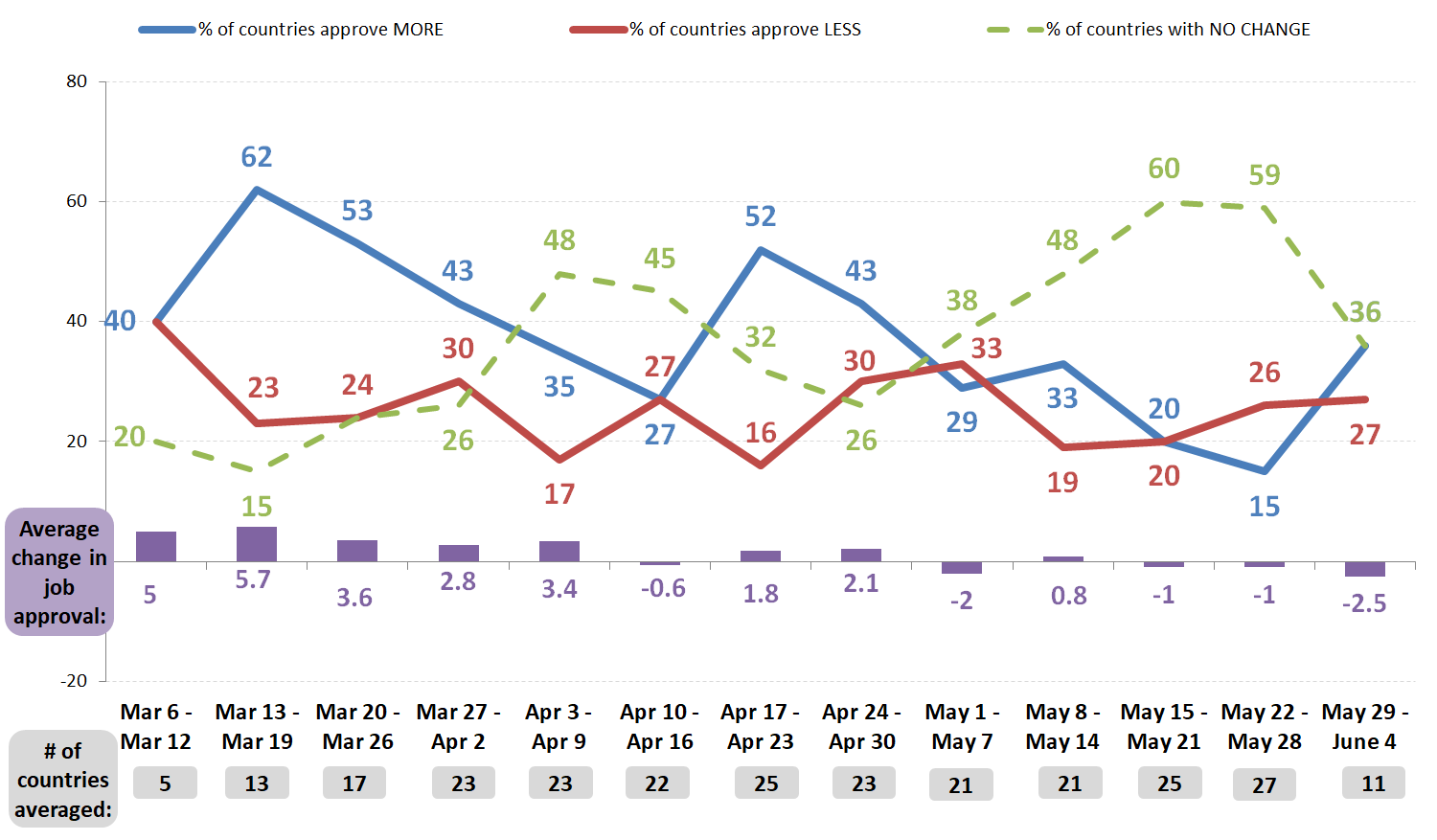

There is also a notable and sustained drop in worldwide approval ratings for governments on their handling of the pandemic. March saw a significant rise in COVID-19 approval ratings for governments worldwide, as publics rallied behind their leaders in the face of a new crisis. From mid-April through late-May, those approval ratings had largely stabilized.

But this week sees an average drop of 2.6 percentage points in COVID-19 job approval across the 11 countries with relevant polling data. This drop occurs even though slightly more countries this week report major improvements than deteriorations in job approval. Although the number of countries averaged this week is relatively small (11), the 2.5 point decline would be the largest weekly drop in average job approval since these global averages began in mid-March.

Figure 2: % of countries showing increase/decrease in approval of government job on COVID-19

Many factors may be driving this decline. The sharp and continuing global economic downturn may be souring public attitudes generally toward their governments. Rising fears of a second wave of the coronavirus may be leading publics to doubt the effectiveness of their governments’ policies. Or there may be other factors at work. Whatever the causes, it will be important to monitor the rise in public fears about the virus, and the erosion in public confidence about government performance in handling it.

* * *

A note to our readers: We want to let you know we are moving from weekly publication of Pandemic PollWatch to an every-other-week schedule. This set of papers has aimed to summarize and analyze all global polling on the coronavirus pandemic. The volume of that polling worldwide is now slowing down. Some polling outlets that were conducting daily tracking surveys on COVID-19 in particular countries have now pulled back to weekly polls, and some companies that are conducting multi-country surveys on the topic have reduced the frequency of their surveys. With fewer surveys on COVID-19 to analyze, it makes sense to conduct these analyses every other week rather than every week. As always, we appreciate your interest and feedback.

[1] These papers are not exhaustive in summarizing the global opinion research; there are many aspects (e.g., the pandemic’s impact on investments) not discussed here. Instead, we are focusing on selected aspects of available global opinion research, with an emphasis on political implications, and providing links to all polls identified, so others have a resource for their own investigations. Our first eleven installments of Pandemic PollWatch, from March 20 through May 28, reviewed a total of 1,027 polls from 100 different geographies (generally countries, but also polling for Hong Kong and various states and provinces). This week’s analysis reviews an additional 71 polls, covering 60 countries, increasing the total number of geographies with reviewed public opinion data up to 107. Links to all polls reviewed are listed here. As the Appendix notes, the polls reviewed vary significantly in methodology and reliability.

[2] For both Figures 1 and 2, data compiled by GQR; data only compiled for countries having week-on-week public polling on the question shown. Countries only counted as showing an “increase/decrease” if the week’s change is at least 3 percentage points. Average for change in level of concern is not population-weighted across countries. Question wordings may differ somewhat across countries and weeks. In both Figures 1 and 2, the data from previous weeks has been revised slightly from previous editions of PollWatch to reflect late-arriving data.

Appendix

This analysis is based on available global public opinion research on the COVID-19 pandemic. We welcome input from others – including insights about opinion trends and dynamics, and about additional public opinion research that is not included here.

Countries and territories with published public opinion data on COVID-19 at this point include:

- Afghanistan

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belgium

- Benin

- Bolivia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Cameroon

- Canada

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cote d’Ivoire

- Croatia

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Denmark

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Estonia

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- Iceland

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Liberia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Malta

- Mexico

- Montenegro

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- The Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- North Macedonia

- Norway

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Senegal

- Serbia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sudan

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Tunisia

- Turkey

- Uganda

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Zambia

- Zimbabwe

The reliability of the public opinion data from these geographies varies – and affects the analysis – for several reasons. First, some of these countries, such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, are “not free” (according to rankings by Freedom House) and respondents in these countries may not feel free to give their actual opinions in a survey.

Second, some of the polling organizations quoted in these reports may have stronger or weaker records regarding accuracy, methodological rigor, transparency, and other procedural factors that affect the reliability of their findings.

Third, the methodologies used in these surveys vary, and few are “gold standard” quality. The pandemic has driven researchers in most geographies to rely on online surveys, which generally do not have probability-based samples and can suffer from opt-in bias. Sample sizes and quality control procedures also vary across the available surveys.

The eleven earlier editions of Pandemic PollWatch, available here, include links to all the previous COVID-19-related polls summarized in this series.

All polls reviewed so far, including in this edition, can be found in the full bibliography here.